Keep Sake

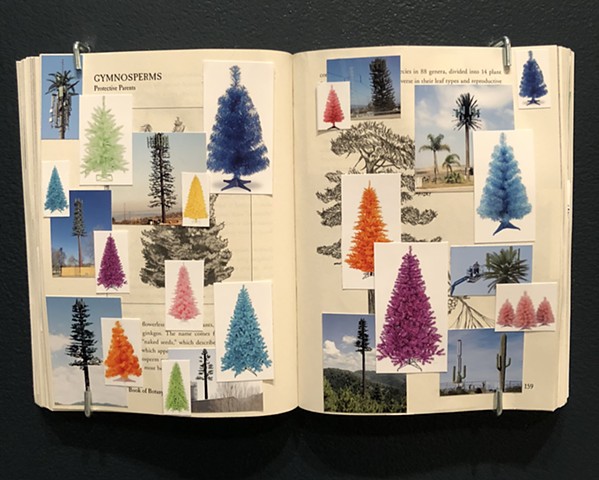

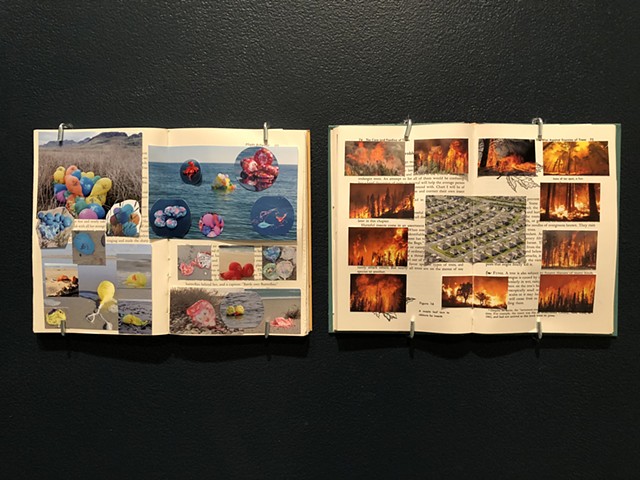

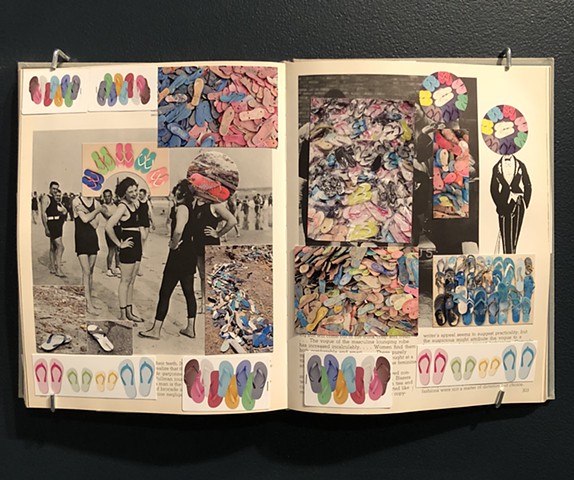

Taking a cue from the Victorian pastime of scrapbooking, as well as the earlier practice of “extra-illustrating” (adding one’s own illustrations to a text as a supplementation or reaction to it), this installation is a collection of myriad reading materials, which are used as the backdrop for an assemblage of images which illustrate a personal response to climate change, climate denial, and a serious lack of our effort to change our ways.

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, scrapbooking was a very popular hobby. Primarily made by anonymous women, they represented a view into the times, illustrating fashion and beauty, but also containing political propaganda, news of the day, innovations, as well as an interest in the natural world (exhibited through samples of pressed plant life, from flowers to seaweed). These were objects that certainly took much time and effort to create. Scrapbooks were and still remain to be viewed as personal narratives, but they represent different ways of thinking about subjects, as opposed to a traditional linear organization of thoughts. What often comes through to a contemporary viewer of these artifacts is an emphasis on typology, or grouping together similar images to create a kind of inventory, almost a visual anthropological study.

Similar to the way in which these young women did not have a voice in society, politics, or the world at large, individual citizens have a difficult time having a voice when it comes to the handling of our environment. In this work we have images of the many examples of ecological damage, pasted in existing writing materials. These materials are the histories and reports of industries who are ecological offenders and polluters of our land, air, and water. It is a deliberate covering over the text to reveal the truth, the effects these industries have had on our planet. At first, the images, by their arrangement on the pages, seem lovely and pleasing. Upon closer inspection, the ugly truth comes through to the viewer.

These books being contemporary collections, one can imagine the maker being obsessed with the process, compiling the images and cataloguing them most likely on a constant basis. It is easy to visualize a constant hunt for materials. Typically, people with obsessive-compulsive tendencies are looking inward at themselves, but this person is bringing the world in and trying to organize it in an order with which he or she can cope, to voice an opinion on the devastation through collected images. They are fanatical scrapbooks with a message as opposed to nostalgic objects. But the question we are left asking is who will see the message? For whom is it intended? We see the installation, but it does seem to be a private space. Somewhere between a personal collection and a political statement, here is but a small voice in the ether.